INDONESIA: Rising Global Demand Fuels Palm Oil Expansion

Based on recently revised official Indonesian government statistics, it is apparent that the country’s rapid expansion of oil palm acreage is continuing in 2010. This is despite escalating environmental and climate change campaigns focused on halting or slowing conversion of forest lands to plantation agriculture in Indonesia, including the newly announced moratorium agreement between Indonesia and Norway. Total area planted to oil palm (immature and mature) in 2010/11 is now estimated at roughly 7.65 million hectares, having increased at an average annual rate of 300,000 hectares over the past 10 years. Whether or not this growth trend is maintained in the future is critically important to the global edible oil market. Palm oil is the single largest traded vegetable oil commodity in the world, global demand is rising rapidly, and few if any countries other than Indonesia are capable of increasing production on an appropriate scale in the near-term. In addition, owing to the fact that palm oil is the world’s cheapest edible oil, it has become the primary cooking oil for the majority of people in the developing world of Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The primary consumer base in these regions is large, growing, poor, and highly price-sensitive in regards to staple food products or commodities. And given there are currently no viable and affordable  edible oil alternatives to palm oil for most of these consumers, any significant reduction in the growth rate of Indonesian production will potentially lead to higher global edible oil prices and increased regional food insecurity. Analysts from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) in Washington and the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta investigated these and other issues during recent travel in Sumatra and Kalimantan. USDA is currently estimating Indonesian palm oil production in 2010/11 at a record 23.0 million tons, up 2.0 million or 10 percent from last year. edible oil alternatives to palm oil for most of these consumers, any significant reduction in the growth rate of Indonesian production will potentially lead to higher global edible oil prices and increased regional food insecurity. Analysts from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) in Washington and the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta investigated these and other issues during recent travel in Sumatra and Kalimantan. USDA is currently estimating Indonesian palm oil production in 2010/11 at a record 23.0 million tons, up 2.0 million or 10 percent from last year.

Indonesian Palm Oil Growth Critical to Global Edible Oil Supply

Palm oil and palm kernel oil are versatile vegetable oils with growing demand from the commercial food and oleochemical industries. Besides its role as a major Asian cooking oil, palm oil is increasingly being used in processed foods, cosmetics, soaps, pharmaceuticals, industrial and agro-chemical products, and as a feedstock for biodiesel. In 2010/11 USDA forecasts that palm oil (including palm kernel oil) will supply roughly 36 percent of total world edible oil consumption, compared to the major alternative oil (soybean) comprising 29 percent. An estimated 74 percent of global palm oil usage is for food products and 26 percent for industrial products. The largest consumers are India, China, EU-27, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Thailand, and Nigeria – which together account for roughly 72 percent of total world consumption.

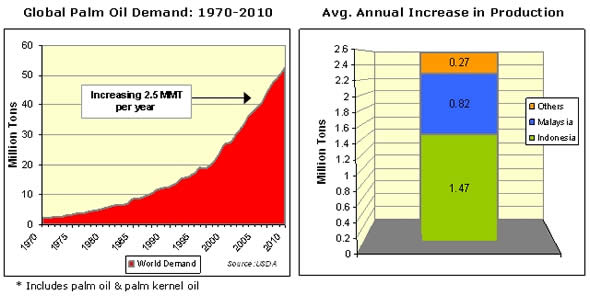

Over the past 10 years total global edible oil demand has increased at a rate of 5.5 million tons per annum (6.25 percent), while palm oil demand on its own has grown by 2.5 million tons or 9.5 percent. The escalating increase in worldwide demand for palm oil has largely been satisfied in recent years through equally rapid growth in the world’s two largest producing nations, namely Indonesia and Malaysia. Indonesia, however, has been responsible for the majority, supplying roughly 60 percent of the total annual increase in palm oil production. If trend growth in global demand continues at current rates, where will the supply come from?

Reliance on Indonesian production is only expected to increase over the next decade as growth prospects in Malaysia decline from a combination of scarce land availability and an aging national tree population (declining yield growth). Indonesia, by contrast, has excellent future growth prospects with a predominantly young tree population, increasing yields, and expanding acreage. It is the only country known to be capable of reliably increasing production by 1.5 to 2.0 million tons a year over the foreseeable future, owing to a vast acreage of still immature trees and a strongly increasing national yield profile. Compared to many other palm oil producing nations, Indonesia has the benefit of a stable political and economic environment, ample land resources and investment capital, appropriate climate, affordable labor, adequate infrastructure, experienced producers, and a well-organized and successful commercial palm oil industry. Given current circumstances, it is apparent that no combination of alternative producing countries could increase production adequately to meet global demand should production stagnate for any reason in Indonesia over the coming years. The international edible oil market, therefore, will become increasingly reliant on Indonesian production, and sensitive to any development that threatens its growth rate.

Near-Term Situation

The palm oil industry in Indonesia is a pillar of the national economy, currently employing over 3.0 million people, contributing roughly 4.5 percent of GDP, and generating export earnings totaling $10.4 billion in 2009. It is a vital agricultural industry which is capable of delivering both substantially higher levels of hard currency earnings and job growth over the next 2-3 decades on the back of a rising world population and increasing demand for edible oils. Palm oil is a highly lucrative agricultural business for both small producers (called smallholders) and commercial growers (companies). Indonesian production costs, inclusive of labor, are very low, averaging $250-300 per ton of crude palm oil (CPO). Profitability for processors is also quite high, and in the current market amount to between $500-600 per ton. With this kind of demonstrated profitability, and armed with a successful plantation development and production model to follow, it is not surprising that there is a huge opportunity and surge of interest from both poor farmers and commercial investors concerning palm oil ventures in the country. Looking at its recent history, both area planted to oil palm and production of palm oil has been increasing rapidly since the mid-to-late 1990’s. Palm oil production has risen by 13.8 million tons or 192 percent over the past 10 years, while exports have increased 331 percent over the same period, from 4.3 million tons in 2000/01 to 18.4 million in 2009/10.

From a purely growth perspective, Indonesia has a lot working for it right now. Planted area has been increasing at a pace of 300,000 hectares a year for over a decade, and the population of immature trees is very large (approximately 1.75 million hectares or 23 percent of total area). The fact that a prolonged surge of plantings began in the past 15 years means that the Indonesian oil palm crop is predominantly young, with most trees yet to come into their most productive years (10-20 years old). Based on official planting statistics from the Indonesian government it is estimated that 55 percent of current national palm acreage is in pre-peak yielding growth stages. This implies that future trend yield growth is likely to continue to be positive, with national yields potentially approaching Malaysia’s record levels in the next 10 years. With this kind of “as yet” unrealized potential built into the national production scheme, Indonesia should be capable of increasing annual production by 1-2 million tons over the same period. The longer Indonesia can maintain its current rate of new area expansion, the longer it can sustain its strong palm oil production growth rate.

Palm Oil Potential

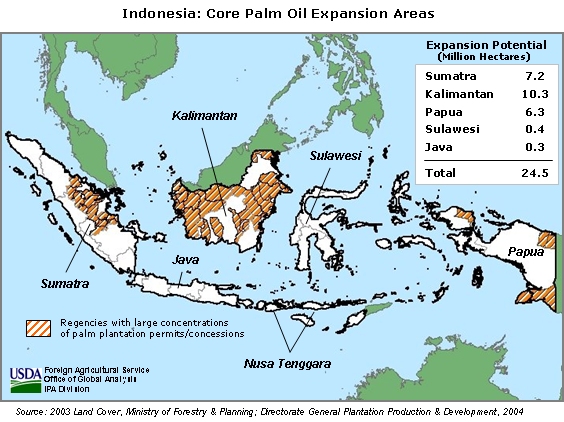

The Indonesian government’s land capability surveys indicate that approximately 24.5 million hectares in the country is potentially suitable for oil palm cultivation. It is estimated that approximated 7.65 million hectares has already been developed, and permits/concessions on another 6.5-7.0 million hectares on as yet undeveloped land have already been issued. No matter where plantation development occurs, the land must be converted from another existing landuse. The two primary land types (as defined by the Ministry of Forestry - MOF) that exist in core areas already targeted for conversion to palm plantations are production forest and dryland agriculture. It is uncertain whether dryland agriculture as defined by MOF means the land is actively cultivated to crops, or is actually degraded former forest lands that were the location of shifting (slash and burn) agriculture. Scientists from the Center for International Forestry Research in Indonesia (CIFOR) report that at least 4.0 million hectares of forested land was converted to oil palm in Indonesia from 1982-2008, though palm plantations are now increasingly being developed on degraded forest lands or cleared land that has been logged. They also point out that most of the lowland forests on both Sumatra and Kalimantan have already been cleared, and of the 5.5 million hectares of land on Kalimantan currently permitted to palm plantation development, only 1.7 million hectares or 25 percent is located on known forested land.

This implies that Indonesia has enough degraded or already logged (cleared) forest land to sustain its current oil palm expansion for the next 20 years. These existing tracts of cleared forest lands are largely concentrated in the core areas specifically targeted for future oil palm plantation development. At current annual rates of increase, therefore, Indonesia could theoretically double current national oil palm acreage by 2030 and increase palm oil production to 60-65 million tons without undue additional damage to remaining forest reserves.

Uncertain Future Outlook

The Indonesian government is in the process of evaluating how to best manage the conservation of its national forest resources, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and lower its contribution to global climate change, while also fostering vigorous national economic development. In regards to the palm oil industry, this has been accompanied by heightened attention and pressure from foreign interest groups as well as a general sense of uncertainty as to where government policy is heading. This uncertainty was particularly pronounced following the May 2010 announcement that the government had signed a climate change and greenhouse gas agreement with Norway, targeted at reducing deforestation in the country and considerably lowering the country’s greenhouse gas emissions (GGE). According to the World Bank, Indonesia is the world’s third largest emitter of CO2 after the United States and China, and 80 percent of its current emissions reportedly stem from deforestation and landuse change, including the drying, decomposing, and burning of peatland. At the outset, the Norway GGE agreement specified a two-year moratorium on all new economic concessions which would result in the conversion of peat lands and natural forest from 2011-2013. The agreement also dictated a longer-term policy and regulatory direction for the country, focusing on an internationally monitored and structured program called reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). Development of a national REDD+ program would involve extensive legal and law enforcement reform concerning the forest and timber sectors, as well as the creation of implementing and forest monitoring institutions. The ultimate goal is to provide Indonesia with an internationally verified measure of the amount and current value of carbon sequestered in its forests, as well as carbon credits for preventing future deforestation. The government of Norway has pledged $1 billion to assist Indonesia in developing the national REDD+ policy, laws, regulations, and institutions.

The predominant issue overhanging palm oil growth prospects in Indonesia at the moment is specifically how the government’s new REDD+ climate change initiative will impact current and future land development policy, and what that means to the oil palm expansion. Will the government honor all existing plantation development permits and concessions? Will it enact a moratorium on new oil palm concessions after the 2013 moratorium expires? Will sizable degraded lands be identified through the REDD+ national baseline land analysis that are suitable for continued oil palm development? None of these questions has been emphatically answered to date, nor has a new draft regulatory framework been announced. Meanwhile, uncertainty regarding what new government laws and/or regulations might eventuate is unsettling commercial palm oil producers and clouding their future investment decisions. In the very short term, it would seem there would be a strong incentive to acquire new permits and/or plant as much acreage as possible before any new land conversion regulations are enacted. What has actually happened on the ground in Sumatra and Kalimantan since May is as yet unknown. The bottom line is that a very successful, immensely profitable industry, which is critical to national economic growth, is now leery of a potentially game-changing shift in government policy direction. And given the increasing importance of Indonesia’s palm oil output to edible oil consumers worldwide, much is also at stake for the international edible oil market and palm oil prices in general as the Indonesian government mulls its options.

Additional information can be found at:

http://www.pecad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2009/03/Indonesia/

Current USDA area and production estimates for grains and other agricultural commodities are available on IPAD's Agricultural Production page or at PSD Online.

|