MALAYSIA: Stagnating Palm Oil Yields Impede Growth

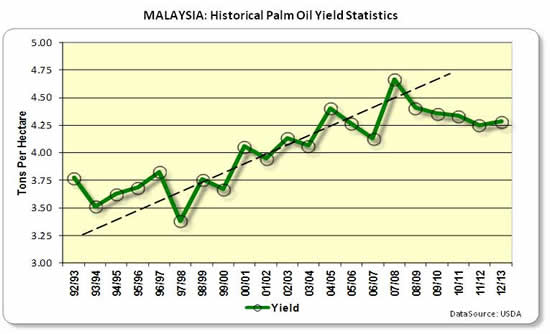

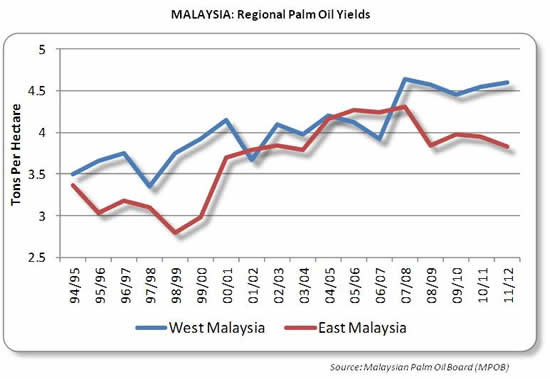

The Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) issued the final monthly production estimate for the 2011/12 USDA marketing year in October 2012, indicating that palm oil production was basically unchanged from the previous year. National average crop yields actually fell 2 percent to the lowest level in the past 5 years, continuing a stubborn pattern of below-trend growth. In fact, palm oil yields have declined steadily over the past 4 years and are now 9 percent below the record 4.7 tons per hectare level achieved in 2008. As a result of the MPOB data, USDA revised its final estimate for 2011/12 palm oil production to 18.2 million tons. USDA forecast 2012/13 production at 18.5 million tons, assuming little or no improvement will occur in national crop yields. The new 2012/13 marketing year began in October 2012 and runs through September 2013.

Historical statistics indicate that Malaysian palm oil yields have typically appreciated over time, with the strongest period of growth occurring between 1998-2008 when yields increased by approximately 4 percent annually. A highly organized commercial industry backed by world-class public/private sector crop research and ample financial resources created the environment for steady incremental improvements in plantation productivity. But in 2009, an unexpected break in the long-term national growth pattern occurred which has persisted to the present day – indicating a new and potentially complicated paradigm has been reached. What happened to the world’s premier palm oil producing industry and what is contributing to the recent pattern of stagnating crop yields?

Problems

Explanations for the abrupt change are varied, being linked to a combination of adverse weather, restrictive government labor and immigration policies, ageing trees, and plant disease. Oddly enough, all of the above except the weather can be remedied by concerted intervention, but solutions will in all likelihood be slow to develop – potentially leading to an extended period of slow or no growth in national production capacity. This unexpected turn of events could last a decade or more, ensuring the Malaysian industry will be even more overshadowed by its neighbor Indonesia, while its global market share of raw and refined palm oil products diminishes. To some degree the government appears satisfied with the status quo, given its resistance to accommodative immigrant labor policy reform, while the industry (including large smallholder organizations) appears to have grown satisfied with current profit margins and continues to provide insufficient wages and benefits to attract enough plantation workers from Indonesia – its primary competitor and the origin of the majority of its immigrant labor pool.

Ageing Tree Population

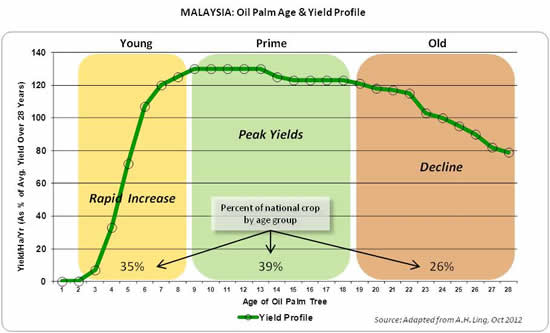

Oil palm is a perennial crop, with trees potentially producing economically viable volumes of fresh fruit bunches (FFB) over a lifespan of 30 years or so. Peak crop yields are achieved from the age of 9-18, and gradually decline thereafter. At present it is estimated that 65 percent of Malaysia’s total oil palm area is between the ages of 9-28+, while 26 percent is at least 20-28+ years old. This implies that the vast majority of trees have already reached or passed through their peak yielding years, and that the inevitable future decline in their FFB output will act to further suppress national average yield growth.

The typical solution to this problem is to have a consistent management plan to eradicate and replace old trees with new high yielding varieties (HYV) on an ongoing basis. Unfortunately, high international palm oil prices over recent years have reportedly suppressed normal replanting rates; as many growers resisted replacing old but actively producing trees at a time of record profits. Young seedlings typically require nearly 8 years to reach peak output capacity, and taking area out of production for 3 or more years did not make good economic sense under the circumstances, especially for smallholder producers. The genetic yield potential of the older trees is also significantly lower than that of cultivars available today and to new cloned varieties being developed. The longer the lag in replanting these older cultivars, the greater long-term delay in improving national average yields.

The government recently reported that about 8 percent of the national crop area or 365,000 hectares is currently 25-37 years old, and that over the next ten years approximately 126,000 hectares of additional trees each year will continue to enter this “old age” category. The backlog of underperforming trees, therefore, is growing. Most of these old trees are located in peninsular west Malaysia and the eastern province of Sabah, where the industry has been concentrated for the greatest period of time. To combat this problem the government is committing over US$135 million in 2013 to jump-start a national oil palm replanting program targeting smallholder producers in both western and eastern provinces. In total, the government hopes to achieve a replacement rate of 100,000 hectares per annum by providing grants to smallholders covering the cost of replanting, while also providing a monthly subsistence allowance of US$157 to independent growers with less than 2.5 hectares for a period of 2 years while their young trees are totally unproductive. In addition to the government sponsored smallholder program, it is assumed that privately held commercial palm oil companies will also replant upwards of 100,000 hectares per annum, resulting in a net 200,000 hectare per annum total replanting scheme. If that target is successfully reached, Malaysia could theoretically eradicate the backlog of old trees by 2018 and reignite the national palm oil yield growth rate by 2020.

Labor Shortage

In 2012 Malaysia reportedly has a total of over 5.0 million hectares of oil palm plantations, consisting of 4.3 million hectares of mature and 0.7 million hectares of immature oil palms. At an average planting density of 135 trees per hectare, this means that there are approximately 675 million individual trees being hand-harvested, fertilized, pruned and otherwise cared for by a largely immigrant labor force. Just imagine that.

The total oil palm plantation labor pool was estimated by the government in 2012 at roughly 491,000 workers, of which 76 percent were from other countries (the great majority from Indonesia). And yet plantation operators in recent years have been plagued by a recurring shortfall in labor supply, especially regarding those who hand-harvest the FFB from trees and collect the heavy fruit bunches for transport to the mill. In other words, the shortage is concentrated in personnel areas directly influencing per hectare returns. Fruit bunches that are left unharvested rot on the trees, while those that are not collected and delivered in a timely fashion to the mill also spoil, thereby artificially depressing annual crop yields. Despite being produced by the tree, they are unrecoverable and lost to the production/processing chain.

The Incorporated Society of Planters Malaysia (ISPM) recently reported that the national plantation labor shortage is most acute in the eastern provinces of Sabah and Sarawak, while the chairman of the Sarawak Oil Palm Plantation Association (SOPPOA) confirmed that the labor supply in his province was 20-30 percent below current industry requirements. The eastern labor shortage was recently reported to have caused losses of 15 percent, specifically owing to rotting palm fruits in both Sarawak and Sabah (which collectively account for 45% of national production). The value of this loss was estimated by SOPPOA at roughly US$1.2 billion. Coincidentally, eastern Malaysia is exactly where historical statistics from the MPOB indicate that average palm oil yields have been declining the greatest since 2008.

The Malaysian government has been working at cross-purposes with the plantation industry in an attempt to reportedly reduce social and security problems related to undocumented immigrant workers in major urban areas, while it is also interested in reducing the country’s dependence on foreign labor. Malaysia reportedly has the greatest dependency on migrant labor of any country in Asia, with roughly 21 percent of the workforce being temporary immigrants. The government’s efforts to limit the time-period migrants can be employed in Malaysia (5 years), more strictly control the issuance of work permits, and the rising cost of annual employer-paid levies have made it increasing difficult for industries to recruit sufficient laborers. In the past, many Malaysian companies, including those in the palm oil sector, have had to resort to hiring people without proper documentation or work permits. Periodic crackdowns and increased government scrutiny has caused a lot of friction in the industry, and has heightened concern amongst potential migrants. Meanwhile the average wage levels offered for plantation workers by the palm oil companies are low, ranging from approximately US$300 per month in western Malaysia to US$260 in eastern provinces. These rates are increasingly uncompetitive with those in neighboring Indonesia, where there is also a lower cost of living and family members are allowed to cohabitate on the plantations. The incentives for unskilled labor to seek employment in Malaysia are rapidly deteriorating at the same time that the palm oil industry in Indonesia is booming, which is a recipe for continued labor shortages inside Malaysian oil palm plantations. The industry does have the capacity to largely overcome this problem, by offering more generous wages and medical/educational benefits to migrant laborers. Some industry watchers have even suggested Malaysian companies explore profit-sharing plans as an additional inducement to attract and keep a dedicated labor pool. However, to date the palm oil industry has been loath to increase their labor-related outlays despite extremely healthy annual gross margins estimated by the MPOB at 60-80 percent. Until both the government and plantation companies modify their positions and policies toward the labor force, the problem of large-scale yield losses through unharvested/unprocessed fruit bunches will continue. This problem also has the potential to mute any progress made in the replanting campaign mentioned above. If the current labor pool cannot successfully harvest the current crop of FFB at current yield levels, how will it harvest even greater volumes from higher-yielding trees in the future?

Plant Disease

A common soil borne fungus called Ganoderma, which can infect oil palm trees, is increasingly becoming a concern for plantation operators in Malaysia. Ganoderma is a genus of wood-decaying fungi found throughout the world, affecting all types of woody trees, including oil palms. Ganoderma infections cause a disease called Basal Stem Rot (BSR). This disease is lethal, with the fungus gradually colonizing the lower 4-5 feet of the trunk of the palm tree, rotting it from the inside. Infected trees will often exhibit wilting or desiccated leaves and eventually a severe decline in the production of fresh fruit bunches. The fungus also forms conk-shaped mushroom bodies on the exterior of the trunk which release spores to nearby soils and trees. Once the spores germinate, they form fungal threads which grow over the roots of the oil palm tree and penetrate their tissue. The fungus then migrates to the lower section of trunk near the soil line, colonizing and decaying the palm trunk tissue, gradually increasing in size and spreading higher up the center of the trunk.

Ganoderma has the capacity to cause significant yield losses well before it has actually killed an oil palm, while its spores can spread through wind and water to ever increasing areas of a plantation once it has been introduced. It can arrive on the soil/roots of a transplanted seedling originating from a nursery, or be endemic to a particular location where a plantation was developed. Meanwhile BSR disease reportedly can kill 80 percent of oil palm stands in an infected area within 15 years of the crop being established. Worldwide studies indicate it can prosper on any soil type and may be able to survive indefinitely in the soil. Land affected by Ganoderma is usually recommended to be left idle or rotated to other crops for a period of several years to help restrict its spread and to reduce the severity of future outbreaks. But this practice is rarely followed in Malaysia owing to the sizable investment that both smallholders and commercial companies have made in developing the land for long-term mono-cropped oil palm, as well as the large potential short-term profits from palm oil and its derivatives. Current management protocols usually focus on destroying individual diseased trees within a plantation and attempting to eliminate as much of the spore-producing bodies as possible. This is followed by replanting of the previously diseased site. In practice, however, once the spores or fungus are established in the soil, replanted palms usually succumb to the disease earlier in their life cycle.

Ganoderma was first identified in Malaysian oil palms in the 1920's in very limited locations. During that time it primarily attacked trees of very advanced age (30+ years). The BSR disease which was then largely isolated to primarily coastal producing areas has since migrated inland and is currently reported to be present in virtually every province in both eastern and western regions. BSR is also now affecting oil palms of every age, from nursery seedlings to those of advanced old age - indicating it has gradually adapted over the decades to changing environmental conditions. Disease-affected areas are now widely scattered or dispersed throughout the country's plantations, though the annual incidence of diseased trees is still relatively low - estimated to be affecting less than 4 percent of total planted oil palm area. Though the disease is only having a marginal impact on current palm oil production at the national-scale, the troubling fact is that it is spreading to greater areas each year and there is as yet no known treatment capable of protecting the oil palm trees. It is apparent that his fungal disease has the potential to become a greater threat to the Malaysian palm oil industry in coming years, unless better management practices are developed and widely adopted or an effective fungicide treatment is discovered.

Current USDA area and production estimates for grains and other agricultural commodities are available on IPAD's Agricultural Production page or at PSD Online.

|